Successful Management of Acute Nitrobenzene Poisoning With Oral Methylene Blue in a Resource-Limited Setting: A Case Report

- Post by: admin

- April 21, 2025

- No Comment

DR Dwijen Das1 Dr Ranjit Ray2

PROFESSOR AND HOD1 POST GRADUATE TRAINEE2

Abstract:

Nitrobenzene is a toxic aromatic compound commonly used in industrial and agricultural products. Ingestion can result in severe methemoglobinemia, a potentially life-threatening condition. We report a case of a 19-year-old female who presented with acute methemoglobinemia following ingestion of 300 mL of 20% nitrobenzene solution. Due to limited availability of intravenous antidotes, she was successfully treated with oral methylene blue and intravenous ascorbic acid. This case highlights the viability of oral methylene blue as an effective alternative in resource-limited settings.

Introduction

Nitrobenzene is an aromatic compound used in the manufacture of dyes, paints, and agricultural chemicals (International Programme on Chemical Safety [IPCS], 2003). Upon ingestion, it is rapidly absorbed and converted into metabolites that cause oxidative stress, leading to the formation of methemoglobin, which lacks oxygen-carrying capacity (Martínez et al., 2003). The standard treatment for methemoglobinemia is intravenous methylene blue (Walter-Sack et al., 2009); however, in many resource-limited settings, this formulation is not readily available.

Case Presentation

A 19-year-old female presented to the emergency department 20 minutes after intentional ingestion of approximately 300 mL of a 20% nitrobenzene solution used in agriculture. She developed central cyanosis with blue discoloration of her face, tongue, and extremities, and complained of breathlessness.

On examination, she was drowsy but responsive. Vital signs revealed heart rate of 60 bpm, blood pressure of 120/82 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 29/min, and oxygen saturation (SpO₂) of 84% on room air. Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis showed chocolate-brown blood with pH 7.37, PCO₂ 40 mm Hg, PO₂ 50 mm Hg, HCO₃ 23 mEq/L, and SpO₂ of 85%. Hemoglobin was 10 g/dL, and other blood parameters were normal. A diagnosis of acute methemoglobinemia was made.

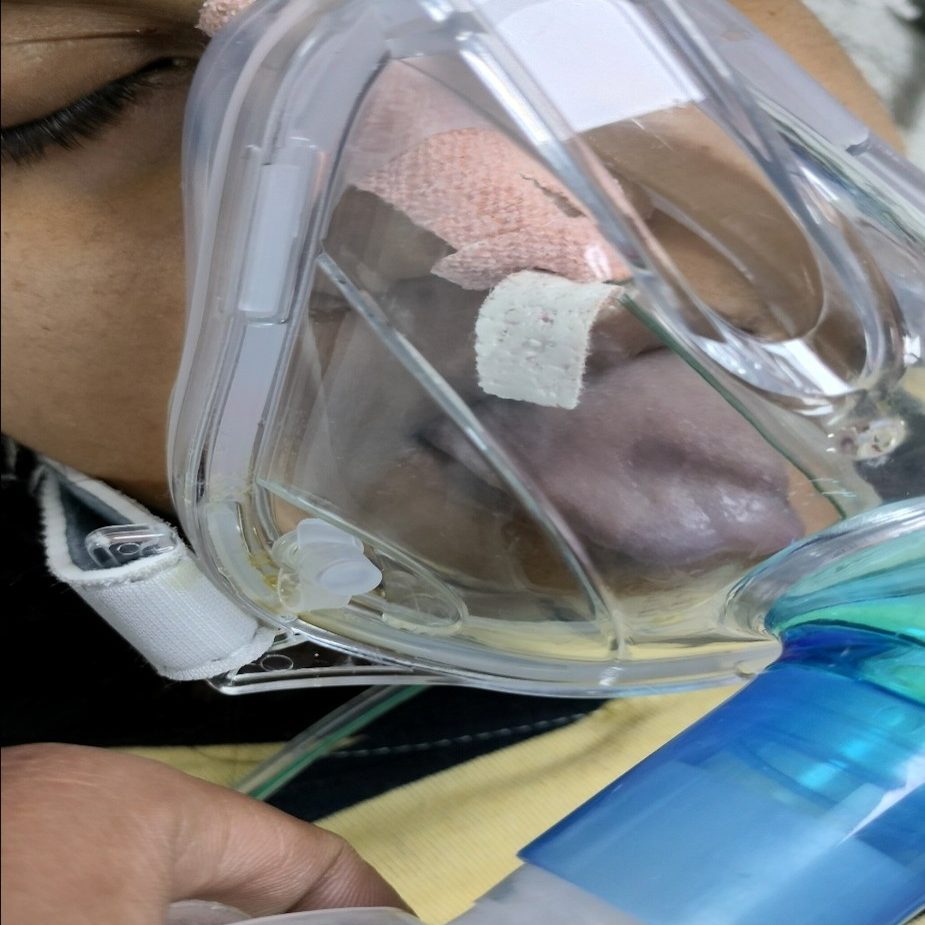

METHYLENE BLUE VIA NASOGASTRIC

TUBE

Management and Outcome

In the absence of intravenous methylene blue, oral methylene blue was administered via an orogastric tube at a dose of 2 mg/kg, repeated after 4 hours for a total of 3 doses. Intravenous ascorbic acid (1 g every 8 hours) was concurrently given (Siba & Lalit, 2017; Shrestha, 2020).

Following initial treatment, SpO₂ improved to 97% within 2 hours but declined again to 85%, requiring repeat dosing. By day 2, oxygen saturation improved to 90% on room air, and by day 3, it reached 95%, at which point the patient was shifted from the intensive care unit to the general ward.

Discussion

Nitrobenzene is highly lipophilic and accumulates in the liver, brain, and blood (Lee et al., 2013). It oxidizes hemoglobin to methemoglobin, converting Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺, rendering it incapable of transporting oxygen (IRIS, 2007). As a result, clinical signs such as cyanosis, low SpO₂, and chocolate-colored blood appear.

Although intravenous methylene blue is the standard therapy, oral methylene blue has demonstrated bioavailability of approximately 72% (Walter-Sack et al., 2009). In this case, oral administration was effective in reversing hypoxia. Vitamin C further enhances recovery by acting as an antioxidant (Siba & Lalit, 2017).

This report supports the growing evidence that oral methylene blue can be a viable alternative in emergencies, especially in settings lacking intravenous access (Shrestha, 2020).

Conclusion

Oral methylene blue, in combination with intravenous ascorbic acid, is an effective treatment for nitrobenzene-induced methemoglobinemia in settings where intravenous methylene blue is unavailable. Early recognition and aggressive management remain critical for patient survival.

References

International Programme on Chemical Safety. (2003). Nitrobenzene: Environmental health criteria 230. World Health Organization. http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc230.htm

Integrated Risk Information System. (2007). Toxicological review of nitrobenzene. United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/iris

Lee, C. H., Kim, S. H., Kwon, D. H., Jang, K. H., Chung, Y. H., & Moon, J. D. (2013). Two cases of methemoglobinemia induced by the exposure to nitrobenzene and aniline. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 25(31), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-4374-25-31

Martínez, M. A., Ballesteros, S., Almarza, E., Sánchez de la Torre, C., & Búa, S. (2003). Acute nitrobenzene poisoning with severe associated methemoglobinemia: Identification in whole blood by GC-FID and GC-MS. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 27(4), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/27.4.221

Siba, D. P., & Lalit, M. K. (2017). Successful treatment of nitrobenzene poisoning with oral methylene blue and ascorbic acid in a resource-limited setting. Toxicology International, 24(2), 216–219. https://doi.org/10.4103/toxi.toxi_34_17

Shrestha, N. (2020). Management of nitrobenzene poisoning with oral methylene blue and vitamin C in a resource-limited setting: A case report.

Walter-Sack, I., Rengelshausen, J., Oberwittler, H., Burhenne, J., Mueller, O., & Meissner, P. (2009). High absolute bioavailability of methylene blue given as an aqueous oral formulation. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 65(2), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-008-0563-2